Editorial

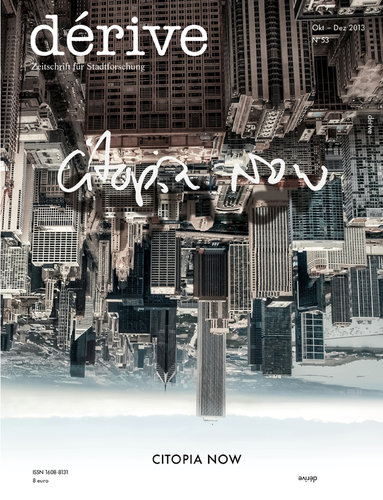

Herbert Marcuse hat 1967 in einem Vortrag vom Ende der Utopie gesprochen. Damit gemeint waren Utopien im Sinne von unmöglich zu verwirklichenden Visionen. Schließlich, so Marcuse, seien alle Voraussetzungen für eine neue Gesellschaft bereits gegeben: »Alle materiellen und intellektuellen Kräfte, die für die Realisierung einer freien Gesellschaft eingesetzt werden können, sind da.« Henri Lefebvre wiederum stellte in seinem ebenfalls 1967 veröffentlichten Aufsatz Le droit à la ville fest: »Das urbane Leben hat noch gar nicht begonnen«. Seit 1967 sind 46 Jahre vergangen, höchste Zeit, die Dinge ernsthaft in Gang zu bringen. Wir haben, wie wir von dérive finden, lange genug auf die »freie Gesellschaft« und das »urbane Leben« gewartet. Es wird Zeit, mit der Umsetzung zu beginnen und an den Ansätzen, die es in vielen Bereichen schon gibt, weiterzuarbeiten: Citopia NOW, das Motto des urbanize! Festivals 2013, widmet sich ebenso möglichen Strategien zur Erlangung des urbanen Lebens wie diese Ausgabe von dérive, die als Festivalausgabe und theoretisches Begleitheft zum Festival fungiert.

Um eine Ahnung zu bekommen, wie die freie Gesellschaft bzw. eine Assoziation freier Individuen aussehen könnte, hilft es zusätzlich zur Kritik an den bestehenden Verhältnissen auch Situationen zu schaffen, die die Alltagsperspektive vergessen lassen und neue Blickwinkel eröffnen können. Margaret Crawford und Mark Purcell haben darüber aufschlussreiche Texte geschrieben, über die im einleitenden Artikel zu lesen ist. Für beide bildet Lefebvres Recht auf Stadt eine wichtige Inspiration. Für Crawford sind es spontane Interventionen, die das vermögen, was die SituationistInnen Situationen schaffen genannt haben: Sie schaffen Bilder, die sowohl neue Möglichkeiten erahnen lassen genauso wie sie Bekanntes in einem neuen Licht zeigen können. Purcell versucht mit Lefebvres Recht auf Stadt und Chantal Mouffes Konzept eines agonistischen Pluralismus Wege in die urbane Gesellschaft aufzuzeigen.

Das hat sich auch Peter Marcuse mit Re-Imagining the City critically erfolgreich vorgenommen. Er zeigt Praktiken und Potenziale unserer gegenwärtigen Gesellschaft, die einen pragmatischen Ansatzpunkt für die befreite Gesellschaft bilden könnten. Als Beispiel dient ihm dabei jene Ausnahmesituation, die der Tornado Sandy letzten Winter in New York geschaffen hat. Dieses Beispiel ebenso wie das von Christian Teckert in seinem Artikel angeführte 3/11 Erdbeben in Japan 2011 zeigen, dass die von Katastrophen geschaffenen Situationen zu ähnlichen Wahrnehmungs-Verschiebungen führen können, wie bewusst herbeigeführte Perspektivenwechsel durch bewusstes, urbanes Handeln. Sowohl Sandy als auch 3/11 haben zu breitem Handeln jenseits von kapitalistischer Inwertsetzung und zahlreichen solidarischen Initiativen geführt, die über den Anlass hinaus als Anregungen für neue, bessere Verhältnisse dienen könnten.

Einen wichtigen Teil des Schwerpunkts nimmt das Thema Mobilität ein. Katharina Manderscheid analysiert die Veränderungen in der Verbindung zwischen Mensch und Automobil und überlegt, in welche Richtungen diese Entwicklung führen könnte. Für wen wird die Mobilität der Zukunft Vorteile bringen? Wer droht dabei unter die Räder zu kommen? John Urrys Text widmet sich dem Rohstoff, der das 20. Jahrhundert geprägt hat wie kein anderer: das Öl. Es geht Urry vor allem darum zu zeigen, dass wir im Interesse aller besser heute als morgen lernen sollten, ohne Öl zu leben und unsere urbanen Gesellschaften dementsprechend neu zu organisieren.

Christian Teckert, dessen Ausgangspunkt wie schon erwähnt das japanische 3/11 und die daraus folgenden, von ArchitektInnen initiierten Bottom-up-Initiativen sind, stellt aktuelle (Wohn-)Projekte in Japan und Shanghai vor, die u.a. zu Verschiebungen im Verhältnis von öffentlich und privat führen und damit neue Perspektiven für den Umgang der StadtbewohnerInnen miteinander und mit dem Raum eröffnen. Auch Manfred Russo widmet sich in seiner Serie Geschichte der Urbanität ausgehend vom Thema Kapsel diesmal über weite Strecken der japanischen Architektur und Lebensweise.

Stichworte dazu sind Kisho Kurokawa und die asiatisch-vitalistische Bewegung, Technoutopien und Hyperindividualismus, aber auch Peter Sloterdijks Foam City und Peter und Alison Smithsons heterotopischer Urbanismus.

Now Urbanism lautete das Motto eines interdisziplinären Teams an der University of Washington, das in einer dreijährigen Forschungsarbeit zu Fragen der Stadt der Zukunft gearbeitet hat und zum Ergebnis gekommen ist, dass der Schlüssel für die Stadt der Zukunft im Heben der Potenziale der gegenwärtigen Stadt liegt.

Quer durch die vorliegenden Artikel von Citopia NOW gibt es natürlich auch Rückblicke auf vergangene utopische Visionen einer befreiten (urbanen) Gesellschaft, also eine Prise Citopia Then, wenn man so will. Am Beispiel von Halle-Neustadt ist das in dieser Festivalausgabe ganz ausführlich nachzulesen: Als sozialistische Planstadt in der DDR gegründet, feiert Halle-Neustadt 2014 bereits ihr 50jähriges Bestehen. Peer Pasternack hat dazu akribisch geforscht und zeigt uns, wie sich die DDR damals die sozialistische Stadt und damit ihre Citopia vorgestellt hat. Der Titel von Pasternacks Beitrag – Die eindeutige Stadt – zeigt schon, dass für die BewohnerInnen nicht viel Spielraum abseits von Top-down-Vorgaben vorgesehen war.

Uns bleibt somit nur noch die Empfehlung, einen Kalender zu schnappen und einen Blick auf www.urbanize.at zu werfen. Das Festival-Programm von urbanize! hält von 4. bis 13. Oktober 2013 zahlreiche Angebote (Vorträge, Diskussionen, Workshops, Filme, Interventionen, …) bereit, sich über dieses Heft hinaus mit Ideen für die urbane Gesellschaft auseinander zu setzen.

Visionen willkommen!

Christoph Laimer und Elke Rauth