Editorial

Small town Europe

Most architects and critics have more affinity with big cities than with the countryside. The inappropriate urban entries for village locations in the latest Europan competition are only one illustration of this contention. The motto of architectural insiders seems to be, ëthe bigger the city, the better and more beautiful it isí. Another indicator is terminology: any reasonably big city or even an amalgamation of two or more medium-sized cities, is all too readily dubbed a metropolis while the same linguistic inflation quickly promotes what used to be called a metropolis to the status of megacity or metacity.

One consequence of the almost obsessive affinity with the big city is a tendency to detect urbanity everywhere, even where there is no city to be found. This was borne in upon me when I read Citt‡ di latta (1997) in which Italian architect Paolo Desideri described how, on his weekly journey from Rome to Pescara, driving across one of the least populated areas of Italy, he noticed that there were always some evidence of habitation. This led him to conclude that the contemporary city is everywhere. Similar perceptions of the unending city can be found all over Europe: the Randstad in the Netherlands, the Flemish ënebular cityí, the double city of Vienna-Bratislava, Actarís interpretation of Catalonia as Hypercity, the west coast of Portugal as linear city and so on. In USE (Uncertain State of Europe), Stefano Boeriís Multiplicity has extended this way of seeing to the entire continent: Europe as a city that never ends.

The idea of Europe as one big urban region reflects a way of looking at things that bears all the hallmarks of professional tunnel vision, comparable to that of the economist who sees rational transactions in every aspect of daily life. The reality is that although 75% of Europeans live in urban areas, the continent makes a very poor showing in global metropolitan tables. In Arjan van Susterenís 2005 Metropolitan World Atlas, only 20 of the 101 metropolises featured are European and that includes three artificial constructions ñ Antwerp-Brussels, Randstad Holland and Rhine-Ruhr ñ as well as a number of cities that are not usually regarded as metropolises, such as Oslo, Le Havre and Genoa. The only European cities to make it into Van Susterenís fifty biggest cities are London (no. 11), Moscow (18), Rhine-Ruhr (19), Paris (23), Istanbul (24), Randstad (38) and St Petersburg (50).

However much professionals would like to see Europe as a region of metropolitan allure, the reality is that the European territory consists for the most part of cities that from a global perspective are medium-sized or small. While that is no reason for architects and critics to quell their fascination with the dynamism of mega- and metacities like Sao Paolo, New York and Tokyo, it does suggest that it is time they recognized that the specific European condition needs to be looked at and managed in a different way. (Hans Ibelings)

Inhalt

On the spot

News and observations

• PÉRIPHERIQUES' refreshingly low-tech circulation building for the Pierre and Marie Curie University in Paris (FR)

• Sir Norman Foster lands in Russia with plans for New Holland island in St Petersburg and Rossiya Tower in Moscow (RU)

• Update: four young Hungarian practices

• In Lyon (FR), Patrick Bouchain and Loïc Julienne have built a dance centre in the form of a gigantic shed for controversial choreographer Maguy Marin

• Reality check: Jürgen Mayer H.'s refectory building in Karlsruhe (DE)

• Interview with Tanja Rajic of Expeditio, an organization that aims at raising public awareness of a better quality living environment Europe's youngest nation Montenegro

• The spectacular Zollverein School of Management & Design in Essen (DE) by Japanese architects SANAA is the first completed building on Zeche Zollverein, a former mining area

• and more...

Start

New projects

• British car manufacturer Vauxhall invited Moxon Architects to envision a service station of the future

• In Tyrol (AT), Johannes Wiesflecker has developed the first business park to combine living and working

• Sergey Skuratov Architects redefine Moscovian luxury with the design of an apartment building in Moscow (RU)

• With a utopian proposal, Sarah M. Miebach and Rico M. Oberholzer are among the winners in a student competition to redevelop a vast industrial complex in Vockerode (DE)

• „Hysteric ballroom“ by bube architects is the most audacious winner of the „Simplicity“ competition held in Almere (NL)

• KHR arkitekter's serpentine shaped centre for health education in Copenhagen (DK) returns as much quality space to the Danish capital as it will occupy

Interview

Secretly beautiful

Veronique Boone and Lars Kwakkenbos interview Christian Kieckens, a Flemish architect whose work ranges beyond mere architecture. As the driving force behind Stichting Architectuurmuseum, he casts a critical eye over the Flemish architectural scene

Ready

New buildings

• PPAG's weekend house in Zurndorf (AT) is distinguished by its elephant skin

• In their design for a school in Pederobba (IT), C+S Associati use multiple colours to good effect

• With an apartment building in Tallinn (EE), 3+1 architects prove that the suburban dream can be realized downtown

• Alexandros Livadas' Supreme Court in Nicosia (CY) exemplifies a new period of modernization in Cypriot architecture

• Pedro Gadanho and Nuno Grande give their personal view of their collaborative design of a weekend retreat in Carreço (PT)

• MTM Arquitectos have built an extension to the School of Pharmacy in Madrid (ES)

• Terry Pawson turns a defunct Magistrates Court in London (GB) into a distinctive office complex

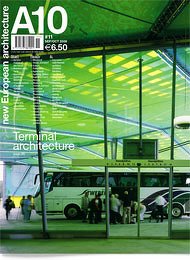

• The more one looks, the more Knapkiewicz & Fickert's coach terminal in Baden-Rütihof (CH) becomes an intriguing adventure

• Mestura arquitectes' police station in Barcelona (ES) plays with the standard connotations of such a programme

• Geninasca Delefortrie architects' private house in Chabrey (CH)

• Marjan Zupanc has turned the brief for a shopping centre in Celje (SI) into real architecture

• With one of his first realizations, Chris Briffa has reconciled a new housing type with a block of typical maltese townhouses in Mosta (MT)

Eurovision

Focusing on European countries, cities and regions

• Southern Italy has generated a determined group of architects who know not only how to work as an architect, but also how to interpret the situations in which they work, assuming a strategic role

• Claes Caldenby, editor of the Swedish architectural review Arkitektur for almost 30 years, responds to Claes Sörstedt's article on „arrogantly modest“ Sweden in A10 #6 and explains the merits of being boring

• Twenty reasons to visit Nizhny Novgorod, Russia's unofficial architectural capital, formerly known as Gorky

• Office: Elliott Wood Partnership's suburban office on a tight plot in London (GB)

• Profile: Arup Associates

Out of obscurity

Buildings from the margins of modern history

A new section focusing on buildings in the margins of modern architectural history. First up, one of the editor's favorites: Koen van der Gaast's railway station in Tilburg (NL) of 1965