Editorial

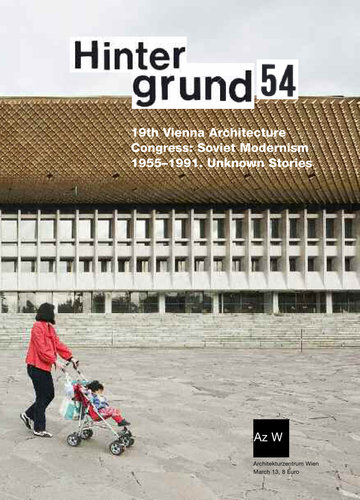

On 24 and 25 November 2012, the 19th Vienna Architecture Congress took place at the Architekturzentrum Wien. Bearing the same title as the exhibition, it explored the unknown stories of Soviet modernist architecture from 1955 to 1991. As with the exhibition and the publication accompanying it, the event focused first and foremost on issues relating to the regional specificities of this architecture.

Experts from the independent successor states of the former Soviet republics addressed phenomena – some occurring in various republics, others limited to only one – that took place on the periphery of the union in spite of the centrally organised Soviet planning system. Together with the large number of international visitors in the audience, diverse themes were discussed that had never been dealt with in this form and on this scale outside or even inside the former Soviet Union. Scholars from Western Europe, Canada and the United States added their insights. A delegation from the Russian Union of Architects based in Moscow charmingly succeeded in directing attention to Russia for at least part of the time by holding the „Last Congress of Architects of the USSR“ in Vienna.

The questions that were discussed in the four panels – „Capitalism versus Communism. The Architecture of Modernism in East and West“, „The Soviet Heritage: National or Russian?“, „Local Modernisms. Centrifugal Forces in the Architecture of the USSR“ and „Built Ideology“ – can be roughly summed up as examining the following themes: the influence of Western Modernism on the work of Soviet architects and the integration of Soviet Modernism into international architectural history; the central theme of local differences, that even in the post- Soviet age have an effect on the preservation of the architectural heritage; and the manifestations of Soviet ideology in architecture and urban planning.

From the 1950s on, a dialogue between architects from East and West gradually emerged. The socio-economic problems following the Second World War and the reconstruction efforts confronted capitalist and socialist societies with similar problems. The shortage of housing and the lack of infrastructure were issues dealt with on both sides by large-scale housing projects. However, the Cold War perspective still informs the reception of the Modernism from the Eastern bloc. Post-war Modernism has yet to be seen from the angle of a dialogue between East and West. It thus hardly comes as a surprise that prejudices – such as, that the architecture of the Soviet Union was largely dismal and uniform and characterised by endless rows of pre-fab buildings – have remained up to the present, and also correspond to the perception these countries have of themselves. Many references to the transfer of knowledge from West to East were made during the Conference, but a more in-depth examination of their mutual influence still seems to be lacking.

The question as to a national art and thus also a national architecture was one of the key concerns throughout the entire Soviet period. (For all the connotations associated with the word „national“, it cannot, in the context of the Soviet Union, be replaced by „local“ or „ethnic“). The slogan „national in form, socialist in content“, so widespread during the Stalin years, briefly lost its relevance during the political „Thaw“ under Khrushchev only to once again gain significance under Brezhnev. This slogan was supposed to convey – both within the country as well as to the outside world – that the Soviet Union was a single family consisting of 15 republics, in which more than 120 peoples had their place and could find ways to develop their own culture. In reality, however, this policy was subject to the strict control of the centre, that is Russia, which ascribed to each nationality a fixed place within the hierarchy. It is important to remember that in all of the former republics one can speak of a more or less forced membership in the Soviet Union, even if the political constellations were very different and there were local forces everywhere that backed the system. The policy of Sovietisation and culture thus moves us into a post-colonial discourse.

Many (ethnically) „non-local“ architects worked in Central Asia in particular. The demand for the national could often only be met through the use of decorative elements that were recaptured in a new context. Even if, for instance, folkloric ornaments were integrated in mosaics or sun shields that covered every possible building, this usually had little to do with the traditional lifestyle of the local population, nor did it respond to the difficult climatic conditions. In his text architectural theoretician Boris Chukhovich, born in Uzbekistan and now a resident of Canada, examines the roots of the Soviet approach to the „Oriental“, locating them in the sketches of the avant-garde from the 1920s. His reflections can be read on pages 31–9. Following his lecture a fascinating dialogue developed between him and architect Andrey Kosinskiy, whose work in Uzbekistan was the basis of Chukhovich’s reconstruction of the colonial character of Soviet architecture in Central Asia. Kosinskiy expressed his appreciation for the serious interest in his work, but he insisted that his only goal was for the architecture to be „udobna“, that is, comfortable for its users, and that the form had emerged from this.

The situation is very different in the Baltic region. There, architecture was understood to be an expression of national identity, but one that was part of European culture. Scandinavian works served as models and a latent opposition towards the Soviet system was also evident. As Estonian art historian Mart Kalm explained, the anti-Soviet stance was ambivalent, since in reality it collaborated with Soviet power; the Baltic countries were certainly complimented by the attention their „more beautiful architecture“ received.

In Estonia, in particular, the way of dealing with the architectural heritage is exemplary. But as Lithuanian art historian Marija Dre˙maite˙ pointed out, the buildings of post-war Modernism in Lithuania are seen less as a Soviet legacy than as a national legacy that was built by local architects. Buildings from the Stalinist period, on the other hand, are seen as an alien „Russian“ heritage. The acceptance or rejection of a certain architectural „time layer“ was also related to the extent that this architecture corresponded to the worldview of a society. For this reason perhaps, the functional and expedient architecture of the post- Stalin era finds a more positive echo in the Baltic countries.

In the Caucasus as well, local architects have been instrumental in shaping the architectural scene. Especially in Georgia and Armenia the contemporaneous modernisation and renationalisation of architecture begun in the Khrushchev era and accompanied an aspiration for national autonomy. This is the theme of the Georgian architect Levan Asabashvili’s text on pages 41–7. Today’s neglect of the architectural heritage of the period of Soviet Modernism in these countries could be explained by the idea that it is easier for the former republics than it is for Russia to evade political responsibility for the Soviet past. This is often perceived as something „that happened to us“ while having „little to do with me“. Thus the architectural legacy from the Soviet period has at times been perceived as „alien“, „non-native“ or „Russian“.

Dimitrij Zadorin, an architect from Belarus, described how architecture was being streamlined in Eastern Europe, while at the same time what was „national“ was being reduced in significance – it was applied, as needed, as a decorative element similar to the themes of the „Great Patriotic War“ or the „cosmos“. In Lukashenko’s Belarus, Europe’s last dictatorship, Soviet architecture is positively assessed in official propaganda, which can be simply explained by the government’s political adherence to the old party line. Even ideologically influenced building types such as Soviet memorials are cultivated there and maintain the same function. In other successor states buildings with anachronistic functions such as those for political education or pioneer palaces are either torn down (like the building for political education by architect Raine Karp in Tallinn) or given a new function. Only in very rare instances is there an accurate reconstruction – the case of the former Museum of the Revolution in Vilnius that today houses the National Gallery being one such welcome exception.

Children’s camps, too, can be found in the category of ideologically motivated building types, since their function was, after all, to not only accommodate the children of working parents but also to inculcate in the next generation the spirit of „Soviet patriotism“. In addition to school work, great importance was attached to extra-curricular activities. A vacation spent under the state’s wings lent itself particularly well to cultivating a collective socialist mind-set. In his lecture (pages 49–57) the architecture critic Wolfgang Kil compared the reconstruction of the former showcase pioneer camp Artek with the recreation of the educational institutions of the Nazi regime, but also with a Kibbutz in Israel, thus questioning the continued use of ideologically motivated buildings.

In addition to the contributions of the experts, the comments and lectures of the architects, most of them from Russia and having worked in the USSR, contributed significantly to an understanding of the phenomenon of Soviet Modernism. At the end of the congress a joint petition was formulated to endorse the preservation of the often-neglected buildings from this period. Parallel to the 19th Vienna Architecture Congress, the international ICOMOS conference „Between Rejection and Assimilation. The Architectural Heritage of Socialism in Central and Eastern Europe“ took place in Leipzig. This shows that the architecture of the former socialist states is also being increasingly addressed in the international discourse on the preservation of the architecture of post-war Modernism.

Last but not least, the international audience, which showed untiring perseverance and active interest, also proved that the 19th Vienna architecture congress was on a highly topical subject.

Katharina Ritter, Ekaterina Shapiro-Obermair, Alexandra Wachter