Editorial

Optimism

Like many things in this world, architecture magazines tend to fall into one of two categories. Most of them deliver good news. They feature outstanding architecture and draw attention to interesting new developments. A small minority of magazines focus on bad news, berating the profession, and the purveyors of good news, with everything that is amiss. The first category reports what is happening, the second finds fault with what is happening and occasionally indicates how it could be done better. However useful the latter may be, A10 belongs resolutely to the first category. And not simply for the sake of disseminating good news. This magazine springs from the hopeful and consoling notion that architecture is a sign of optimism. Shelter is a basic human need and architecture is but a refined version of that elemental form of protection something that not everyone and not every society can afford. Europe enjoys a privileged position in this respect given that so many of the four hundred million inhabitants of this continent can permit themselves the luxury of architecture, or are at any rate not excluded from it. They can experience it, if not as owners, then as users of buildings and the urban space.

The construction of a building demonstrates faith in the future, if only because of the willingness to invest durably in the future that is manifested in such an act. A well-designed and well-maintained built environment in short, architecture is moreover a sign of a society’s worth. Those who can afford it, owe it to their position to serve the collective interest, and although architecture is often intended for the greater honour and glory and for the pleasure of the individual who commissions it, in the best cases it is also, and above all, a social act. Generally speaking, architecture serves a

collective interest.

In many European countries there is fertile ground for such architecture. And in many European countries this kind of architecture does indeed flourish. Two major determining factors in the emergence of such architecture are the level of prosperity and the degree of openness of the society concerned.

In most European countries the level of prosperity is good or at least improving, notwithstanding numerous pockets of poverty, including in generally wealthy countries like the United Kingdom.

But openness is another matter, even in the democratically governed European Union. Which makes it all the more remarkable that even in countries where the current political climate is bleak, where corruption, xenophobia, discrimination and narrow-minded nationalism hold sway, that even in places where the guarantee of shelter does not extend to all citizens, the optimism of architecture lives on.

Inhalt

On the spot

News and observations

• The opposite of the typical white beach lounge: Thomas Heatherwick’s East Beach Cafe in Littlehampton (UK) is a rough and rusty steel shell

• Zaha Hadid’s design for Eleftheria square in Nicosia (CY) is cause for a political debate

• Book review: „Superuse“, on constructing new architecture by shortcutting material flows

• 14 new bar-pavilions by T2a in a former harbour area by the Danube river in Budapest (HU)

• Before & after: The Dutch embassy in Rome (IT) by Cepezed

• Reality check: VS architects’ „Nice Living“ housing scheme in Bratislava (SK)

• and more...

Start

New projects

• ALA’s remarkable „strange birds“ in Helsinki (FI) provide a challenge for Finnish contractloon professionals

• Christian Kerez has won the competition for the new Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (PL)

• Urbanoffice and Bauart create space for dialogue with their Haus der Religionen in Bern (CH)

• Mehmet Kutukcuoglu and Ertug Ucar solve the spatial needs of Istanbul Maritime museum in Istanbul (TR) in a clever and pragmatic way

• As-if and raumzeit have designed a swimming pool in Montafon (AT) that looks like an artifical landscape

• A futuristic info tower by Kusus & Kusus will hopefully inspire similar plans elsewhere around Berlin’s Schonefeld airport (DE)

Interview

Manuelle Gautrand

Manuelle Gautrand does not believe there is such a thing as a feminine architecture. „I have been interviewed more as a woman than about my architecture. By now, I’d like to be seen not as a woman but as an architect“

Ready

New buildings

• Through their poetic pragmatism 3LHD have managed to insert a large building into the sensitive context of pitcturesque Bale (HR)

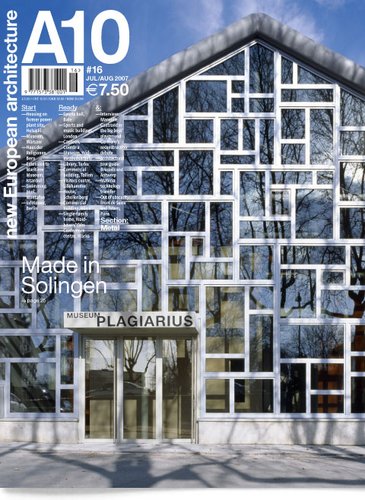

• Reinhard Angelis extended an old warehouse for the new Plagiarius museum in Solingen (DE), which is dedicated to copies, fakes and other froms of product piracy

• dRMM show the way in the English programme for „Building Schools for the Future“ with their renovation and extension to Kingsdale School in London (UK)

• Although LGLS’s canteen is the smallest building on the University Campus of Coimbra (PT), it has great social significance

• Emlépont, a museum about the communist past in Hódmezovásárhely (HU) got a futuristic building designed by Attila F. Kovacs

• JKMM has given Turku (FI) yet another architectural work it can be proud of

• Alver Trummal Architects’ 4 Ravala Avenue expresses Tallinn’s desire to build a new city (EE)

• Carl-Viggo Holmebakk designer a simple and clear entrance building for the estate of Sigrid Undset in Lillehammer (NO)

• Ulrike Mayer and Urs Hüssy made a 200-year-old house and barn in Schellenberg (Liechtenstein) look brand new

• NEO_arhitekti’s answer to a very constrained context for a commercial building in Uzice (CS) was to expand inwards

• The Tetris school in Genolier (CH) by IPAS looks like a playful fortress

• In Waidhofen/Ybbs (AT), a small medieval town, Hertl.Architekten cause a sensation with a modern rooftop superstructure

• Jasinski Kruszewski Architects have found an elegant solution for a brewery theme park in the town of Warka (PL)

Section

Metal

As from the Bronze and Iron age, metals have played a fundamental role in the development of human civilization. Nowadays, thanks to the diversity of available metals, the ever-growing number of alloys and new processing techniques, metals offer architects virtually unlimited design freedom

Materia

The Internet has opened up a new world for many people, not least architects.

Innovations in industries that were formerly a closed book to most architects, are suddenly accessible, thanks to the Internet. More than ever before, techniques and materials derived from, among others, aviation, shipping, mould-making, the medical and technical textile industries, can be transposed to architecture

Eurovision

Focusing on European countries, cities and regions

• Germany’s reconstruction debate comes to a head: Frankfurt’s Old Town is to be rebuilt

• A tour Antwerp and Brussels’ „Beacons of Renaissance“ (BE)

• Profile: Philippe Rahm’s experimental buildings illustrate his idea that „architecture follows climate“ (CH)

• Home: Pieter Weijnen’s blue house in IJburg, Amsterdam (NL)

Out of obscurity

Buildings from the margins of modern history

Jean-Philippe Hugron goes back to the Front de Seine in Paris (FR), which started as a modernist project, but became infiltrated with postmodernism in the form of the Totem tower

Sports hall, Bale

Through their poetic pragmatism 3LHD have managed to insert a large building into the sensitive context of picturesque Bale

Bale (Italian name Valle, meaning valley) is a town in western Istria with a population of just one thousand. Unlike other small Istrian towns, which tend to huddle together, Bale is scattered across a low hill in a green valley, so rather than presenting a close-knit medieval mass, the town has evolved as a free arrangement of volumes on the remains of a Roman castrum. The silhouette is dominated by a church very typical of the North Adriatic area and an atypical Renaissance palace belonging to the local patrician family. Together with traditional houses, half-urban and half-rural in character, they form the context of the new sports hall by 3LHD studio.

In this somewhat sleepy environment which has been spared the waves of tourists a seaside setting would have drawn, it is legitimate to talk in terms of „context“, „tradition“, „regionalism“ and „composition“, for this is definitely not a dynamic modern environment, but a time capsule of sorts. That character adds value to the context, and it is logical to strive to preserve its timeless picturesque quality. The current harmony could easily be jeopardized by property developers and tourism, which is why this latest addition to the composition, similar in size to the church, had to be inserted with great care. 3LHD studio architects have succeeded in that.

The size of the hall was determined by the dimensions of the basketball court (the design standard for this type of building) and some additional programme. However, the architects manipulated the dimensions in relation to the context by partially burying the hall, locker rooms and the corridor connecting the hall with a nearby school building. The act of digging the soil, evoking entrenched medieval castles, is emphasized by an earthen embankment on the outer sides (towards nature) of the composition. On the inner, town-facing side of the cubic volume, light penetrates the hall through a large cut-out level with the square. This opening turns the corner, slanting across the side of the building and converging with the embankment in a single point. The building is set off from the surrounding, non-designed public space by a narrow belt of smooth concrete. Despite its taut, angular form, it meets its environment quite gently.

The client’s demand that the hall be completed within eleven months could only be met by using prefabricated elements for both loadbearing construction and facade. The facade, which incorporates a dry-stone motif, exemplifies 3LDH’s poetic but pragmatic approach to architecture. In addition to the long dry-stone walls that are the result of the laborious excavation of stones from the soil to make it usable, the Istrian and Dalmatian countryside still boasts a number of prehistoric dry-stone buildings, the so-called kažun in Istria and bunja in Dalmatia. These cylindrical buildings are similar to the „trulli“ of Apulia, only smaller in size and intended not for living, but for storing agricultural tools.

Even though dry-stone structures are confined to the land, introducing the motif as decoration into an urban environment, however minor, can still be seen as logical in this particular context. Thanks to the carefully modelled masses and the intelligent cladding, the simply articulated volume blends perfectly with its surroundings – both urban and rural.

This project is part of a recent wave of regulated, tourist-oriented development initiated by a local entrepreneur with good connections at the local and national level. If the new sports hall is an architectural indicator of such development, Bale and its architects are on the right track.A10, Fr., 2007.07.27

27. Juli 2007 Krunoslav Ivanisin

verknüpfte Bauwerke

Sporthalle Bale

University canteen, Coimbra

Although LGLS ’s canteen is the smallest building on the University of Coimbra’s third campus, it has great social significance

A canteen is a natural meeting place on a university campus. The lunch break, usually understood as the moment one escapes from classes, is welcomed by one and all and this should be reflected in the architecture. Though sometimes neglected, even in a country like Portugal which is so proud of its culinary achievements, here in Coimbra it was accorded due attention. The new canteen by LGLS aims to celebrate the importance of that moment of the day.

The canteen is situated on the new Campus III of the University of Coimbra. Given that this is the oldest university in Portugal, established over 700 years ago, it naturally carries a significant amount of symbolism and tradition. Its historic buildings are the symbol of the city itself and the two new campuses bear an architectural responsibility to support these values.

Campus II (engineering) is nearing completion while Campus III (medical sciences) is still under construction. Both display a lively architectural ensemble, as nearly all the buildings are the result of national competitions which gave younger architects an opportunity to emerge from amongst the work of already established offices.

Appropriately, given its social importance, the canteen is one of the first buildings to be finished on Campus III. Situated on the edge of the campus, looking away from the city and facing its main road ring, the canteen is the built result of a competition won back in 2001 by the Lisbon-based architectural practice, LGLS.

Conditioned by a sharply sloping site and a limited budget, the project quickly evolved into a play of scale, space, light and colour that offers us a surprisingly large and luminous interior wrapped in what at first sight seems to be a fairly compact external package.

Public access is at the upper level. The building then develops downwards, generating its strongest external moment at the opposite end from the entry point, thereby twisting the meaning of „main facade“ and allowing for an internal shift in scale that makes the light-flooded refectory so impressive.

The composure displayed by the building when approached from within the campus, with its low-profile main elevation hidden behind a sun-filtering pergola, is a key moment in the promenade architecturale that runs through the building, down to the main refectory. You end up following the light in search of the space where everybody congregates.

The internal colour scheme, tied to distinct ceiling heights, clearly defines the internal functions and instinctively organizes the users. The upper floor contains the washrooms and the cafeteria (both painted in black) which ends in a full-length balcony above the main refectory and kitchen below. This translates into two differentiated canteen systems for the students (one tiled in blue with a high ceiling and one tiled in red with a low ceiling) and a restaurant for teachers and university guests (panelled in wood). The restaurant does not belong to the same hierarchy as the rest of the programme and that explains the difference in the finishing material. It also has a separate external entrance. The bottom level is technical, including storage spaces, staff changing rooms and so on.

An artful juxtaposition of simple architectural elements turns the smallest building on the campus into a well-proportioned environment for socializing in the middle of the academic day.A10, Fr., 2007.07.27

27. Juli 2007 Anton Eguerev da Silva

verknüpfte Bauwerke

University canteen, Coimbra

Commercial building, Uzice

NEO_arhitekti’s answer to a very constrained context is to expand inwards

The town of Užice lies in the narrow basin of the River Djetinja and is enclosed by the Zlatibor and Tara mountain ranges. A similar constriction affects „Textil“, a commercial building created from the expansion of a conventional 1950s warehouse. Textil has therefore continued to expand internally for most of its past and by doing so it has retained, yet jazzed up, its industrial charm. The new building has literally swallowed the old one, while further approaching the outer limits of the site.

It is a project that is quite unusual for Serbia, where construction in recent years has been characterized by arbitrary and unplanned architecture. What might be self-evident elsewhere – clarity of concept and quality of execution – is new and exceptional here. Simplicity is still yearning for recognition in Serbia.

Still, the success of this design is due not only to the architects, Snežana Vesnic´ and Vladimir Milenkovic´, but also to the client. The planning process proceeded in a spirit of co-operation and mutual understanding. From the start, the company recognized that architecture could contribute considerably to its corporate identity. Established in 1991, Textil trades in (what else?) textiles, which it imports from Italy, China and further afield and sells on to the wholesale and retail trade in Serbia.

The building is located in Užice’s industrial zone between the motorway, the railway, warehouses, a football field and a cemetery. To make matters worse, the industrial zone is in the process of being transformed into a commercial centre. The only constants seem to be change and heterogeneity. How to respond to such a setting? The architects delivered what they themselves describe as „anti-design“ in reaction to the surroundings and context. Ignoring all those external factors they are powerless to change, they concentrated on the interior. The result is a building with an interesting perforated facade that reveals nothing of its interior life. What has been achieved is a very efficient spatial organization and in contrast to this programmatic severity, a rather playful facade which defies its surroundings. Contrast is a recurring theme in this project.

The introverted nature of the building is not only a reaction to its heterogeneous surroundings but a form of protection from the extreme climate which is marked by strong temperature fluctuations, summer and winter. The building consciously makes limited use of daylight as the storeroom requires none and the salesroom and workstations make additional use of a clear and simple lighting concept. The building, three stroreys high, breathes from the inside out: it has its own microclimate, which is regulated by a big, one-storey atrium and eight rooflights on the flat roof. The atrium can also be used as a terrace, accessible from the top floor.

The old and the new complement each other. The storeroom is located in the existing structure, the salesroom and offices in the new. They are united on the outside by the perforated building envelope and inside by the atrium. The construction is a reinforced concrete skeleton. Although the old structure has been completely absorbed by the new one, it is still clearly defined by rectangular columns and visible beams, whilst the new structure utilizes stronger floor slabs, which are supported by circular columns throughout. Connecting the ground floor reception area to the upper-floor offices are two homogeneous, gently coiled concrete staircases. These are the focal point of the public area. The colour scheme alternates between black and white: a black facade, white interior walls and industrial flooring and then black again in the service spaces.

Most of the furniture was designed by the architects themselves and reinforces the black-and-white theme: white in the public areas, black in the office areas. To relieve the stark colour concept and add a little playfulness to the interior, the architects introduced some wall racks and horizontal bars in warm timber tones for a little light gymnastics or perhaps for the unfurling and presentation of textiles, which is, after all, the purpose of this building. A10, Fr., 2007.07.27

27. Juli 2007 Vesna Vucinic

verknüpfte Bauwerke

Commercial building, Uzice