Editorial

Hot spots

The more you know about something, the less inclined you are to hold definite and unequivocal views on that subject. At any rate,

after two-and-a-half years of A10, I find it increasingly difficult to give a categorical reply to the question of where the current hot spot of European architecture is located. Nor do I find it easy to nominate „the place to be“ for European architects in the near

future, although I am still willing to bet that Central Europe will figure prominently in the years to come.

The fact is, that for me as editor of A10, and probably also for regular readers, the magazine’s contents lead to the inescapable conclusion that equally good architects are working all over Europe, producing equally interesting projects and concepts (at best one might disagree about the intrinsic appeal of contemporary architecture). And even though differing economic and cultural conditions mean that the chance of such architecture actually getting built is not everywhere the same, it would be difficult to deny that interesting projects are seeing the light of day all over Europe.

Of course, even today it is still possible to point to some countries and regions – Portugal, Slovenia, Ireland, Austria and the Czech Republic all come to mind – that attract and merit an above-average amount of interest, but none of these countries acts as an epicentre of contemporary development as Barcelona did around 1990, or Switzerland in the heyday of the Swiss box, or the Netherlands at the end of the previous decade. In contrast to a few years back, there is now no country or city in Europe that pre-dominates in all the professional journals, not a single „must see“ that appears on every architect’s travel itinerary. And to the extent that such destinations do exist, they are more likely to be found outside Europe, with China and Dubai the most obvious candidates at the present moment.

The picture A10 paints, of a Europe where interesting architecture is being built all over the place, is not in itself false, but it is only part of the bigger picture. The magazine’s set-up, with every two months a wide geographical distribution in plans and structures, suggests a qualitative homogeneity.

Even a country that is not particularly active on the architectural front, usually manages to produce five or so projects a year that are worthy of publication, and those five may ensure that the country concerned is nearly always present in A10; conversely, this same editorial policy of distribution prevents countries with a rich architectural production, such as Austria or Spain to name but two, from dominating the pages with more than ten or twelve projects in a single year. Hans Ibelings

Inhalt

On the Spot

News and observations

• Santiago Calatrava's Guillemins TGV station in Liège (BE)

• Monopoly-inspired kiosks appear in Madrid (ES)

• Rotor's recycled office in Brussels (BE)

• Update: Scotland

• Colourful student rooms at Krabbesholm Art College (DK)

• Reality check: Centra Nams in Riga (LV)

and more...

Start

New projects

• Silis, Zabers & Klava challenge the traditional image of a theatre in their design of a concert hall in Riga (LV)

• The results of the Proyecto VIVA housing competition in Spain shows that young architects search for innovation via strategic rather than formal processes

• Projektil has designed two very different but equally iconic libraries in Prague and Hradec Králové (CZ)

• Tadeusz Kantor's Art Documentation Centre, alias „Cricoteka“, by Wizja and nsMoonStudio „clashes“ with Cracow's old architecture (PL)

• Marios Economides and Maria Akkelidou won the competition for the Cavo Greco information centre (CY)

• Ski manufacturer Rossignol's headquarters in the French Alps by Hérault & Arnod pays homage to the mountains, but also to technology

Interview

Paul Kahlfeldt

Berlin-based architect Paul Kahlfeldt explains why all architecture is basically the same ever since it has been known that loads are transferred vertically towards the centre of the earth: „That is why the column is a central element in construction“

Ready

New buildings

• Dorte Mandrup Architects evoke warm feelings with a cool sports and culture centre in Copenhagen (DK)

• Raumzeit have given space, colour and a sense of luxury to a youth hostel in Bremen (DE)

• In Tallinn (EE), KOKO architects have placed a glass box on top of the Fahle building, symbolizing its conversion from paper to lifestyle factory

• No w here architects' cathedral choir school in Stuttgart (DE) is not spectacular, but certainly unconventional

• On Malta, Architecture Project has turned a garden into a spectacular outdoor living room

• In Dromahair (IE), Dominic Stevens has realized his ambition for building a house that would literally become part of the Irish landscape

• ZOOM's unorthodox apartment building in Sofia (BU) had to weather a few local storms before being accepted

• Despite its makeshift appearance, MARC's sports club boathouse on Lake Como (IE) was built to endure

• In Joensuu (FI), Lahdelma & Mahlamþki designed a pavilion-like primary school with a „windmill“ plan

• The undulating balconies of RVDM's Glicinias housing in Aveiro (PT) prompt Pedro Gadanho to reflect on how taste changes

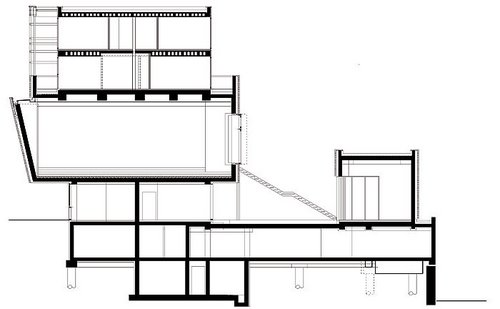

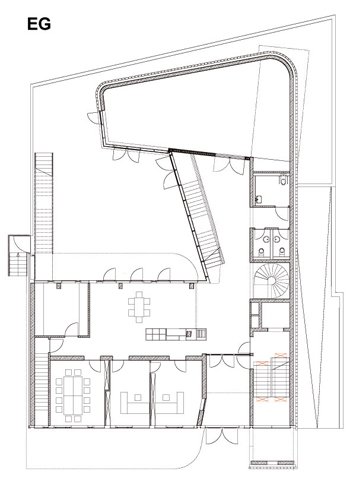

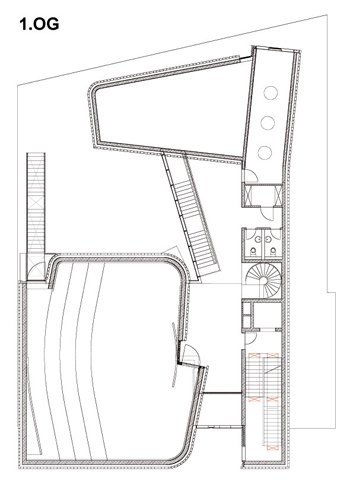

• „A case of cannibalism in architecture“ is what EM2N architect Daniel Niggli calls his conversion of the Stadthof 11 in Zurich-Oerlikon (CH) into a theatre for musicals

• Fast, cheap, non-aesthetic: Catalin Berescu's emergency housing in Dorohoi (RO) is miles away from contemporary fashionable experiments

Section

Climate control

The connection between climate and building has undergone a paradoxical evolution. Whereas houses used to provide their occupants protection from the climate, they must now protect the changing climate from human beings.

Matter

Materia's view on the latest materials

Materials that are light-permeable are usually called „transparent“ or „translucent“, although it might be more accurate to call them „diaphanous“ - of such fine texture as to allow light to pass through; translucent or transparent (from dia-, „through“ + phainen, „to show, to appear“). It is related to „phantom“, something apparently sensed but having no physical reality.

Eurovision

Focusing on European countries, cities and regions

• Over the last few years a trend has been emerging in Dutch architecture that could perhaps be categorized as „unspectacular“. After the visual frenzy of supermodernism and neo-traditionalism, this looks like a choice for the middle of the road. The opposite is true: it signifies a deliberate reticence

• An architectural tour guide of Brno's boxes and anti-boxes (CZ)

• Home: Ilja Skocek's apartment, Bratislava (SK)

Out of obscurity

Buildings from the margins of modern history

Oliver Elser takes a closer look at Gert Hänska's monstrous Research Facility for Experimental Medicine, established with the best of intentions and set down in an almost idyllic landscape location in Berlin (DE)