Editorial

Good intentions

Leo Tolstoy wrote that „all happy families resemble one another, but each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way“. Architects want to make people happy: users, clients, passers-by, perhaps even architecture critics. But architects have an even stronger desire to make something that looks as little as possible like anything else. Those inclined to go along with Tolstoy’s observation, would probably conclude that this is just the very worst route to achieving architectural happiness. Designers, on the other hand, believe that there is no greater architectural happiness than a unique building.

It is entirely to their credit that many architects should want to make the world a better, happier and more harmonious place, although given the permanence and expense of constructing a building, it is really no more than logical. Construction is costly and the lifespan of a building too long for designers not to hope at least for an outcome that feels good. Which perhaps explains why architecture is so far removed from other forms of art like literature, visual art and theatre where there is a much readier acceptance of representations of rootlessness, fear and alienation. They occur in architecture, too – there are enough places that do not make people happy, where people feel uneasy – but this absence of happiness is always an undesirable side-effect, a product of impotence, or simply of unforeseen circumstances.

Obviously, a large part of the built environment suffers from the indifference that attended its creation, but such indifference usually turns out to be more a matter of failure, be it just of the imagination, rather than of evil intent. Perhaps the only exception to this rule is the architectural and urban design cynicism so sadly common in totalitarian states. But most architecture is made with the best of intentions, however counterproductive these occasionally turn out to be.

That kind of counterproductive architecture, not to mention the architecture of indifference, does not appear in architecture magazines, save as a drab, almost interchangeable background against which the happier examples look even more radiant. Which just goes to show that in architecture Tolstoy’s observation about happiness and unhappiness may need to be stood on its head. (Hans Ibelings)

Inhalt

On the spot

News and observations

• Residential harbour developments in Copenhagen (DK)

• European Prize for Urban Public Space to muf’s Barking Town Square in London (UK)

• Helsinki harbour plans cause a stir (FI)

• Will the new Hermitage Guggenheim put Vilnius (LT) on the cultural map?

• Milestone in Serbian social housing (HR)

• Reality check: Palais Thinnfeld, Graz (AT)

• and more...

Start

New projects

• Museum, Gardabaer (IS) by PK Arkitekar

• Oris pavilion, Zagreb (HR) by Andrija Rusan

• Bungee jump platform on water tower, Ploubalay (FR) by Igor Lecomte and Espace Gaïa

• Public centre, Lviv (UA) by Domorinthos

• Hotel, Lernacken (SE) by Space Group

• Department store extension, Graz (AT) by Nieto Sobejano Arquitectos

Interview

Ivan Kucina

Vesna Vucinic interviews Ivan Kucina about the difficulties of being an architect in Serbia. Nevertheless, Kucina remains optimistic: „There is something positive about transition and that is the absence of control.“

Ready

New buildings

• Camping ground, Rimigliano Natural Park (IT) by Archea Associati

• Auditorium and theatre, Villajoyosa (ES) by Jose M. Torres Nadal and Antonio Marquerie

• House, Salzburg (AT) by Flöckner Schnöll Architects

• Social housing, Budapest (HU) by Péter Kis and Csaba Valkai

• Cultural centre, Aarhus (DK) by SLETH Modernism and ET Architecture

• Temporary theatre, Iasi (RO) by Angelo Roventa

• Urban intervention, Bilbao (ES) by ACXT

• School of Economics, Murska Sobota (SI) by Rok Benda, Primoz Hocevar and Mitja Zorc

• Outlet store, Metzingen (DE) by Blocher Blocher

• Town houses, Amsterdam (NL) by Atelier Kempe Thill

• Pavilion, Grammichele (IT) by Marco Navarra

• Cinema, Liège (BE) by architects V+ and engineering firms BAS and B-B

Section

Metal skins

In architecture metal has traditionally been associated with structural properties, with strength, large spans and great heights. Recent decades have seen the development of a new and different approach to the use of metal. Instead of being confined to robust loadbearing structures for utilitarian buildings, steel, aluminium and iron are starting to be used in facades and interiors, including in homes. These are designs which highlight metal’s „softer“ side in subtly worked skins and stylish textiles.

Eurovision

Focusing on European countries, cities and regions

• The power of words: European architectural policy is built on a superabundance of words

• A changing coast: an architectural tour of Croatia

• Profile: Stalker (IT)

• Office: Henning Larsen Architects’ innovative office in Vesterbro, Copenhagen (DK)

Out of Obscurity

Buildings from the margins of modern history

Axel Simon takes us to Eduard Neuenschwander’s 1964 studio in Gockhausen, near Zurich (CH).

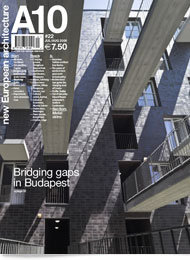

Social housing, Budapest

Rather than laying down rules, Péter Kis and Csaba Valkai’s realized competition design is intended to accommodate changes by its future users.

The working-class area of Józsefváros, Budapest’s 8th district, is currently undergoing a veritable metamorphosis. The biggest and most obvious project is the „Corvin Promenade“, a 22-hectare area that the developers are touting as a second city centre for the Hungarian capital (see also A10 #6). To make room for the many new shops, luxury apartment complexes and office buildings, hundreds of houses, many in a very poor state of repair, were demolished. In 2005, making good on a promise that new housing would be built to accommodate the district’s dispossessed former inhabitants, the Budapest city council and the local district council jointly organized an open competition for a block of social housing on Práter Utca. This street is just one street away from Pál Utca, made famous by the 1969 film adaptation of Ferenc Molnár’s 1906 novel, The Paul Street Boys. Close to the competition site on Práter Utca stands a bronze artwork of the five marble-shooting street urchins of the novel. Little has changed in the one hundred years since the book’s first appearance: the area is still inhabited mainly by lower income earners, including many people from Roma origins.

The competition for the social housing block was won by Péter Kis’s practice. Péter Basa came second, and third prize was shared by the firms of Erick van Egeraat and Tamás Getto. This is Kis’s first social housing project; until now his practice has been best known for its projects at the Budapest Zoo, in particular the Bonsai pavilion, a meticulously detailed glass building whose timber frame was inspired by the bamboo plant. Péter Kis, whose practice is also located within the walls of the zoo, is currently working on the construction and interior revitalization of an artificial rock from 1912.

Kis’s winning Práter Utca design consists of two separate volumes linked by five footbridges, a configuration that allows the normally enclosed courtyard garden to be seen from the street. The district is characterized by closed street frontages that give no hint of the courtyards and green gardens that lie behind. Kis has deliberately exposed one of these gardens to the street. At the same time, he set the block that runs parallel to the street a few metres back from the building line, thereby creating extra public space. Facing onto this expanded sidewalk he placed a number of business premises and a small shop. The setback also allowed him to introduce projecting balconies on this side of the block. Where necessary he added a concrete awning to protect the floor above from flash-over in the case of fire. In his choice of materials for the facade Kis drew inspiration from the dark brick party walls that are another feature of this district. But so as not to imitate them too literally, he opted for a charcoal glazed tile which, while shaped like a brick, is laid in a stack bond. Kis sees his street facade more as an abstract stone curtain than a massive structural wall.

The choice of white synthetic frames for the apartments was motivated mainly by the very limited budget of 480 euros/m². Kis regarded the tight budget as a challenge, especially in light of the fact that he has been working for three years on the design of a very luxurious house for an exceptionally wealthy client.

The subtle interplay between the solid concrete balcony floors and awnings and the delicately detailed steel balcony railings is intriguing, adding a touch of vulnerability to what is at first glance a very robust building. On the day when the photos were taken, the complex had only shortly been inhabited. But the architect is not worried by the fact that the occupants of the relatively small apartments (from 30 to around 60 m²) will probably appropriate the balconies and close them off with rattan matting or, worse still, corrugated plastic sheeting. He is convinced that the building is strong enough – structurally and formally – to survive such interventions. Kis compares the complex to the Colosseum in Rome which has suffered all manner of encroachments over the years, only to emerge all the stronger. Which is why Kis has no intention of issuing any rules for his building. Instead, his architecture is designed to create possibilities and scope for the users. Only time will tell whether the occupants will value and appropriate this apartment block in such a way that it is able to grow old gracefully.A10, Do., 2008.07.31

31. Juli 2008 Emiel Lamers

verknüpfte Bauwerke

Apartment Block Práter Utca

School of Economics, Murska Sobota

Rok Benda, Primož Hocevar and Mitja Zorc designed a building that deserves to become a point of reference in Slovenian contemporary architecture.

After admiring a building in photographs, I’m always a bit afraid I’ll be disappointed when I actually get to see it on site. When I am not, I feel almost gratified. And it is even more satisfying when its users, whom I sometimes meet by chance, tell me that they really enjoy the place. For me this acts as a confirmation that even today, architecture can do more than just excite the architects, fulfil some useful functions or help developers and investors sell their real estate for yet higher prices.

This is what happened during my visit to the School of Economics in Murska Sobota, the easternmost and economically least developed town and region in Slovenia. I was supposed to be guided through the building by the school’s management but as chance would have it, I was introduced to it by a cook, who was taking a break beside the service entrance. She was very pleased to hear that I was interested in seeing the interior and told me proudly, with a strong local accent, that she worked there. She offered to let me in: so I first saw the kitchen and only after that visited the rooms and halls that were meant to be seen by visitors like myself. She and other staff told me that the building was brand new, that they had just started to work there and that it was really great. For them this building was the beginning of something new and promising.

Indeed, the building can be considered a beginning in several ways. Not only because it has just opened its doors but because it offers a new opportunity for many students, teachers and other employees to develop their careers, because it is one of the first recently-realized buildings in a new part of town that is still under construction and because it is part of a new and wider development of the region. It is also a new beginning for Rok Benda, Primož Hoevar and Mitja Zorc, the architects who designed it. This is their first major realization. They received the commission as a result of an architectural competition held in 2002; five years later the building was completed, and just a month ago it earned them the country’s most prestigious architectural prize – the Jože Plecnik award.

This low, compact building houses a complex programme for a Secondary School of Economics, structured in three parts that correspond to the three sections of the building. In the front section we find the main hall, lecture hall and library, the central section houses a cafeteria and the entrance, lecture hall and administration, and the end section contains a gymnasium. These sections stretch and bend along a long, narrow site in such a way as to generate several outdoor spaces. The building opens up to these spaces – parks, gardens and fields – through large glass walls. Particularly now, in middle to late spring, the views are amazing, astonishingly green. As a result, the building appears to be wrapped in a thick, bright green coat such that the cladding material – dark grey ceramic tiles – appears particularly fitting. The choice of material is doubly apt in that the region around Murska Sobota is very rich in clay and is well-known for its long tradition in ceramics and pottery. Perhaps the building’s success can be summarized as its ability to encapsulate various positive qualities of its environment; or, more precisely, to make the best of this environment visible.

Kenneth Frampton once explained that the task of an architectural critic is to highlight certain works and thus help establish them as points of reference in a more general discourse about what architecture is and what it might be in the future. The School of Economics in the remote town of Murska Sobota certainly deserves to become a special point of reference for Slovenian architecture.A10, Do., 2008.07.31

31. Juli 2008 Petra Ceferin

verknüpfte Bauwerke

School of Economics

Cinema, Liège

The city of Liège is in the throes of a renaissance and it has just acquired a new landmark, the result of a collaboration between the architects V and engineering firms BAS and B-B.

In early May, the non-profit association Les Grignoux opened the doors of its new art cinema in the centre of Liège. After more than 25 years of providing the inhabitants of Liège with an alternative film programme, Les Grignoux opted for a new, distinctive face that is an emblem for both the cinema and the city.

In 1999, Les Grignoux, which at that point operated two small art cinemas in the centre of the city, raised the alarm: a huge new cinema complex planned for the outskirts of the city would be the kiss of death for many small cinemas in the city centre. Over the past 20 years, most Belgian cities have seen similar big cinema complexes built on their outskirts. On the one hand they were responding to the growing numbers of people deserting the city cinemas, but on the other hand they contributed to this same malaise. So people in Liège were worried that the new cinema would lead to the demise of cultural and social life in the city centre. The S.O.S. had the effect of making the city aware of its cultural capital. After consulting with Les Grignoux on an action plan to expand its cultural and film-related projects, the city provided financial support for the scheme in the form of a plot of land in the centre of the city. Les Grignoux itself invested heavily and with further support from the Walloon Region, the French Community and the EU the project became a win-win for both parties. Les Grignoux would be able to expand its diverse activities – film shows, exhibitions, concerts and festivities – and the city would acquire another cultural showpiece a mere stone’s throw away from the Opéra Royal and the entertainment and retail centre of Liège.

The Sauvenière cinema is the result of a strong collaboration between the architects V , and engineering firms BAS and B-B. The new cinema stands on Place Neujean, an airy and amorphous white building that appears to float above the street. With its four cinemas and several public indoor spaces, the building embraces a public courtyard garden that is accessible from the shopping arcade behind it and from the ground-floor foyer of the cinema building. The courtyard has become the building’s fifth space and will be used for open-air film shows, concerts and parties.

This multi-functionality also reflects Les Grignoux’s wider purpose. Although the strict standards governing comfort, projection and safety left little scope for variation in the design of the cinemas, the final design is much more than a few black boxes and the requisite circulation. The difference between this cinema and the commercial variety is its relationship with the public: the building is part of the city and the city is part of the building.

The design is characterized by airy social spaces around the four closed cinemas, stacked two on two. The many open circulation areas and foyers invite all manner of encounters, exhibitions and activities in relation to the city. With that in mind, the building is raised above street level and the entrance to the main foyer pushed back beneath the cantilever so that the pavement becomes a genuine „parvi“ or forecourt for the expansive foyer and the bar, setting up a vista from the street to the courtyard where cinema patrons can mingle before and after the film. The ground-floor foyer segues, via a wide, gently raked staircase along the street side of the building, into the next foyer which provides access to the first two cinemas and a view over the city. The third foyer, containing the entrances to the two highest cinemas, has a terrace overlooking the courtyard and is thus more focused on the internal goings-on. The exits of all four cinemas are along the garden side and take the form of long, semi-transparent tubes attached to the courtyard facade.

The dark interiors of the cinemas – with seating in a lively pink-orange-red colour combination – contrast with the light colours of the public areas: white, fluorescent green, beige and concrete-grey. Here and there a few „objects“ have been harmoniously incorporated into the architecture. The green ticket counter, for example, stands in the middle of the ground-floor foyer, with the initial hustle and bustle swirling around it. The third foyer is reached by an „escalier escargot“: an intimate, winding passage through a snail’s house that debouches into airy openness. Even the structure assumes the appearance of a sculpted object. The cinemas, columns and walls have a plastic quality and together form a willed rather than a necessary structure. As such, the building testifies to a well-thought-out poetic approach: a new generation of Belgian architects is busy making its mark.A10, Do., 2008.07.31

31. Juli 2008 Veronique Boone

verknüpfte Bauwerke

Cinema Sauvernière