Editorial

Cultural minority

Generally speaking, architecture magazines are not all that different from car magazines: both devote a disproportionate amount of attention to objects that you rarely if ever see on the street. Who would ever bother to buy an automobile magazine if the contents differed only minimally from what you could see in any parking lot? The same applies to architecture magazines: who would want to read a magazine that features the kinds of buildings that you see all around you every time you step outside your own front door? Even with an editorial policy of deliberately disregarding the architectural equivalents of the latest Porsches, Ferraris and Aston Martins, the projects presented in A10 are poles apart from the average Opel Astra – Europe’s best selling car – which you can see driving down any street in your neighbourhood.

The truth is that most of the projects featured in A10 are exceptions rather than the everyday, run-of-the-mill buildings that stand just outside our field of vision in that unobserved zone that the French writer Georges Perec once so aptly dubbed the „infra-ordinary“.

Seen in this light, A10’s ambition to provide a balanced coverage of architecture throughout Europe, is no more than a shift in emphasis vis à vis the massive exposure already accorded to iconic buildings and to all the other designs by architecture’s top guns. For even though our correspondents together cover the furthest corners of Europe, and even though they consistently ignore projects that are assured of receiving adequate publicity – even then, the works A10 manages to document amount to a very small proportion of building production.

To quote Hans Hollein’s famous statement once again: „anything can be architecture“; but in the end significant architecture, architecture that can be categorized as a cultural deed, manifests itself in only a small percentage of building production. No matter how important architecture may be as a cultural discipline, within the sum total of building production the works of architecture that interest the media make up no more than a tiny minority.

This does not, however, make this minority any less important, because even in an age when the idea of an avant-garde has lost its appeal it can still be classified as a vanguard, a source of inspiration for countless designers who are as unlikely to receive a commission to design an iconic building or to attain starchitect status as they are to own an Aston Martin or a Ferrari. (Hans Ibelings)

Inhalt

On the spot

News and observations

• Zaha Hadid's Nordpark cable railway in Innsbruck (AT)

• In Athens (GR), the New Acropolis Museum nears completion

Urban Center in Turin (IT) hosts tours of once neglected, now transformed industrial sites

• Update: Serbia

• Modern interpretations of old buildings in Brussels (BE) and Stromness (UK)

• and more...

Start

New projects

• A team of international and local artchitects has won the competition for a „City of the Environment“ in Santomera (ES)

• Antwerp (BE) is embracing itself; a 1200-metre-long bridge by the THV NORIANT consortium will finally close the ring around the city

• Hungarian firms win competitions for Pécs, European Capital of Culture 2010

• CAKMAK architects' In Vino winery complex in Modra (SK)

• Carlos Mourao Pereira's sea baths in Lourinha (PT)

• With their design for a distribution warehouse in Staffordshire (UK), Chetwoods Associates prove that a business park can actually be green

Interview

Svatopluk Sládecek

Svatopluk Sládecek, who has been running his New Work studio since 1995, stands out among young Czech architects. His work represents an original architecural strategy in the Czech Republic - instead of following the example of Western designers, he draws his inspiration from the tradition of the Czech periphery (the world of city-yards, farming land, industrial districts, kitsch conversions), transforming tired architectural motifs into contemporary projects. Jan Kratochvil interviews him.

Ready

New buildings

• Behnisch, Behnisch & Partner's spa baths in Bad Aibling (DE) offer wellness to everyone

• Ton Venhoeven's fire station in Den Helder (NL) reasserts the heroic status of firefighters

• PK Arkitektar's apartment building for handicapped youngsters in Hveragerdi (IS)

• In their apartment building in Paris (FR), Beckmann-N'Thepé bring concrete facades alive

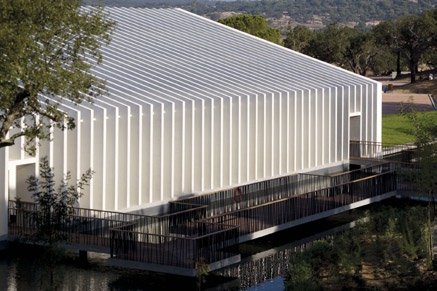

• Promontório's river aquarium in Mora (PT) is helping to launch the local tourist economy in the Alentejo region

• In his design for a housing project in Zagreb (HR), Hrvoje Njiric politely exploits a market-ruled context

• With his wooden villas in Pirogovo (RU), Totan Kuzembayev traces Constructivism back to its Russian origins

• In Ditzingen (DE), Barkow Leibinger used the client's own technology to create a classy gatehouse

• Manuel Ruisanchez's library and Sagrada Familia community centre in Barcelona (ES)

• Brigitte Métra's first solo project is a cultural and sports centre in Dole (FR)

• In Scharans (CH), Valerio Olgiati designed a house without a roof for artist Linard Bardill

Section

Flourishing facades

The term „explosive growth“ has never been more appropriate: in the past fifteen years or so, roofs and facades all over the world, from Tokyo to Chicago, have started sprouting mosses, plants, flowers, shrubs and trees. These „green roofs“ and „living facades“ are regarded as technologically innovative but in reality they are nothing new. After all, according to Greek historiography, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon (near present-day Baghdad), a botanical and architectural artwork counted among the seven wonders of the world, were built as long ago as the 6th century BCE.

Eurovision

Focusing on European countries, cities and regions

• Does the self-willed historicism that seems to hold Islamic religious architecture in its thrall lie in the religion itself? Christian Welzbacher investigates the architecture of Euro-Islam

• Photographer William Brumfield's pilgrimage to the most obscure corners of Russia

• Everybody is familiar with Rome's ancient architectural masterpieces, but what about modern architecture? Giampiero Sanguigni presents a critical tour of 21 projects

• Profile: rising Bulgarian stars I/O

• Home: Peter Jannes' contemporary wooden house in leafy Grobbendonk (BE)

Out of Obscurity

Buildings from the margins of modern history

Roman Rutkowski & Lukasz Wojciechowski take another look at the observatory complex on Mount Sniezka in southern Poland (1959-1974). Designed by Witold Lipinski, with Waldemar Wawrzyniak, it is still a fascinating piece architecture and a stark contrast to the usually gloomy building production of the Communist regime.