Editorial

Shelter, comfort and privacy

If local, regional and national traditions make themselves felt anywhere in architecture, it is in the home. Domestic architecture is heavily influenced by specific social and cultural conventions. These, in combination with climate, give rise to considerable architectural differences between North and South Europe, but also between neighbouring countries and even between north and south in a single country. Yet climate and conventions seem to play no more than a secondary role when it comes to the special category of architect-designed houses and villas, a selection of which can be found in this issue of A10. While these houses may exhibit a certain kinship with local traditions in their appearance and materialization, in programme and use they reflect a universal character.

That universal character has little to do with the archetypical function of the house as the fulfilment of the basic human need for shelter. For the majority of people in today’s preponderantly prosperous and well-organized European societies, the urgency of this need is largely dormant. For the better-off occupants of the architecturally superior houses and villas featured in these pages, the physical need for shelter is a thing of the past; at most the houses they commission contain a derivative of this basic need, in the form of a desire for the psychological security of privacy and the physical pleasure of comfort.

Despite this desire for metaphorical shelter, such custom-made houses usually proclaim a conspicuous lifestyle, to use a variant of the well-known concept of conspicuous consumption introduced by Thorsten Veblen in his famous 1899 book The Theory of the Leisure Class. The private swimming pool, which as this issue shows is as likely to crop up in Gothenburg as in Seville, is one of the traditional symbols of this lifestyle. Most striking, however, is the fact that – at the moment when the photographer dropped by, at any rate – there appears to be an inverse relationship between the number of cubic metres of living space and the quantity of visible worldly goods. The homeopathic dilution of possessions is an even better indicator of affluence than the size of the swimming pool. For while most people struggle in vain against an overwhelming quantity of furniture, appliances, clothes, toys, old newspapers and gadgets around the home, the occupants of these houses can allow themselves what Gerrit Rietveld called the „austere luxury“ of not being constantly surrounded by their possessions. (Hans Ibelings)

Inhalt

On the Spot

News and observations:

• Having previously furnished both the Reichstag in Berlin and the British Museum in London with a new roof, Foster & Partners has now done the same for Dresden’s railway terminal (DE)

• Vienna's MuseumsQuartier has been taken over by 114 Styrofoam blocks, designed by PPAG, which can be arranged in countless ways forming igloos, seats, stages, catwalks, sculptures and mountain • climbing landscapes

• Moscow’s 171st metro station connects the centre to the future financial district of Moscow-City

• Four years of research, two years of repeated announcements from different publishers, recurring discussions about the results – the three-volume book „Switzerland, An Urban Portrait“ had a turbulent life behind it by the time it finally saw the light of day

• The Sea Organ in Zadar (HR) is a system of organ pipes activated by the kinetic energy of the waves breaking against the shore, producing an ever-changing composition

• Reality check: Aurland's viewing platform (NO)

• Update: Torino 2006. For the Winter Olympics, Turin has built new premises, revamped old buildings and upgraded entire districts

• and more...

Start

New projects:

• Siiri Vallner, Indrek Peil and Katrin Koov's competition-winning college building evokes the baroque past of Narva (EE)

• Gudmundur Jonsson designed a cultural centre in Brogarnes (IS), inspired by the Icelandic saga „Egill the Strong“

• With a new gate to Malta, Architecture Project fuses history with renewed urban activity in the harbour of Valletta (MT)

• ARCHTEAM’s new entrance to a municipal building in Hradec (CZ) pays tribute to modernist architect Josef Gocar

• Archea insist that their building „4 ever green“ in Tirana (AL) should be categorized as an „urban tower“, not a skyscraper

• With their designs for a tea pavilion and a forest tower, architectural firms na-ma and SeARCH won an invited competition for the redevelopment of „the most beautiful arboretum in the Netherlands“

• Ex-Archigram member Peter Cook designed a housing project in Madris (ES) with his new practice CRAB

Interview

Urs Primas and the dark side of architecture:

Axel Simon talks to Urs Primas about Switzerland and the future. Primas: „Reflecting sceptically upon the future, addressing undesirable or dangerous plots is necessary. Especially in urban design we should not be operating only with promises of growth but also considering shrinkage or even breakdown scenarios.“

Ready

New buildings:

• Hans Moor's bridges in Rotterdam (NL) have been conceived by means of a design process based on Darwin’s theories

• With his design for a private house in Sigulda (LV), Andris Kronbergs was awarded the best architectural design in Latvia, beating heavyweight rivals

• Lydia Haack, John Hoepfner and Richard Horden have developed „micro compact homes“ which are being tested this year by students in Munich (DE)

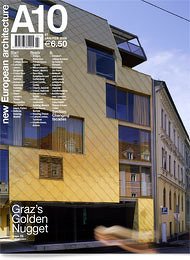

• Golden Nugget in Graz (AT) exemplifies INNOCAD’s all-encompassing approach: development, design and sale

• That Belgian social housing doesn't have to be stereotypical and impersonal, is shown by TEEMA with their project in Merksplas (BE)

• Two villas by Wingårdhs: VillAnn in Kungsbacka and Villa Astrid in Gothenburg (SE)

• Ubaldo & Marisol Garcia Torrente created an urban loft in the heart of Seville (ES)

• JKMM Architects designed a timber church building in Helsinki (FI) with an interior that is both minimalist and invitingly warm

• A remarkably innovative school in Hadsund (DK) by JJW Arkitekter and bjerg arkitektur

• With their design for a private house in Dublin (DE), Boyd Cody Architects prove that a house can be a private refuge and a part of its neighbourhood at the same time

• Allmann Sattler Wappner have converted a listed factory building in München (DE) – mainly for their own use

• In Norfolk (UK), Hudson Architects have built Cedar House – the modern barn par excellence

• Zerozero transformed the greyscale monotony of a housing estate in Presov (SK) with a powerful geometric concept

• Macken & Macken has added a new complex to the Warande Cultural Centre in Turnhout (BE), countering the brutalism of the existing building

• For a double house in Athens (GR), Nikos Ktenas reinterpreted the traditional Greek „katoikia“

Section

Analysing specific aspects of contemporary architecture:

A new feature focusing on specific aspects of contemporary architecture. In this first instalment, a cross-section of changes in the area of the facade.

Eurovision

Focusing on European countries, cities and regions:

• Recent years have seen the emergence of network practices. Jorrin ten Have interviewed three of them: Ocean D, UFO and a-Graft. Pedro Gadanho signals a quiet revolution of „open-source architecture“.

• The dubious proceedings surrounding large-scale urban transformations in Istanbul.

• A10’s Slovenian correspondents take you on a guided tour of the best architecture in Ljubljana

Instant History

Buildings that already get their share of media attention:

According to Ursula Baus, Phaeno Science Center in Wolfsburg is further confirmation of what has been emerging in Zaha Hadid’s recent projects worldwide: rather than producing over-intellectualized buildings, she is becoming increasingly sensitive to the situation at each specific location, offering tailor-made urban and landscape repair.